On AI, biology, and China's prospects for leading the next techno-scientific revolution

Tanner Greer at Scholar’s Stage has written an informative report describing the Chinese government’s ambition to lead the next techno-scientific revolution. In this essay, he repeats his earlier skepticism about the prospects for digital technology to produce such revolutionary advancements.

In my mind the only route by which AI could lead to an industrial revolution-sized disruption is if it unlocks advances in more fundamental industries, such as energy or materials science. Imagine a future where we replace the steel in our skyscrapers with synthetic spider silk—that is the sort of transformation that might justify comparisons to the industrial revolution. AI might open the door to this sort of future, but this is not what most people who make predictions about AI’s economic potential like to talk about.

I would argue that, (1) computing (particularly AI) is precisely what offers the prospect of such a revolutionary advancement, and (2) China is well-placed, but certainly not guaranteed, to lead such a revolution.

To the first point, consider the example of synthetic spider silk. What gives spider silk its unique, remarkable properties is not some chemical element that is unused in synthetic materials, but the protein spidroin. What gives spidroin its special properties, compared to steel or other proteins, is the arrangement of its constituent parts, namely its amino acid sequence. Spider silk has emergent properties derived from highly-optimized patterns of ordinary elements. This is a triumph of evolutionary design over brute force, of information over ultra-high temperatures or pressures. Mass adoption of spider silk will require mastery over the production process, and therefore precise understanding and control of complex protein aggregates.

Many of the most promising areas of techno-scientific research, from metamaterials to biological engineering, are based on this key idea. Metamaterials research typically focuses on identifying nano-scale patterns that give rise to super-materials. The ongoing revolutions in gene editing and protein engineering are due to the extreme diversity of 3-dimensional protein structures that are encoded by DNA sequence / amino acid sequence. The world of bits is the epitome of this phenomenon: the value is not in the silicon, but in its physical layout as prescribed by GDSII files, and in the patterns of digital signals as prescribed by code. Similar transformations in the world of atoms arguably require an analogous ability to program the physical world, including biology, at the microscopic level.

What are China’s prospects of leading such a revolution? China’s advantages and disadvantages in this field parallel its overall economic strengths and weaknesses, but with a few key differences. AI model training requires data, compute, and AI research talent. Chinese LLM efforts are at a data disadvantage compared to US LLM efforts, due to the greater quality and quantity of English language data on the Internet and English-trained data annotators. In biology, in contrast, the picture looks different. China has rapidly achieved a competitive advantage in the contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) space, with companies like Wuxi AppTec, which suggests an ability to scale biological measurement and production at lower cost than the US. At the same time, China is behind the US in terms of bioanalytical capabilities and access to computing resources.

This is analogous to Taiwan’s lead in the semiconducter manufacturing space. Just as TSMC, by scaling its foundries, was able to not only reduce costs but improve yield, scaling in the life sciences has both cost and quality benefits. If you have a measurement device that you employ once per week to measure a particular characteristic of proteins, you will quite easily miss reproducibility problems (“batch effects”) in your assay that lead to statistical confounding. But if you use that same device dozens or hundreds of times per week, not only are you amortizing the fixed cost of that machine by more frequent usage, but you are giving yourself the chance to fix problems with that machine and with your processes which use it. Elimination of such batch effects is a key bottleneck in transitioning from artisanal biochemical data collection to AI-scale data generation. (To be clear, the level of complexity of Wuxi’s work is more similar to that of semiconductor packaging, rather than that of foundries like TSMC.)

A second advantage that China enjoys with respect to biological data generation is in the real estate infrastructure of life science. Stephen Smith (aka MarketUrbanism) shared a link to an interesting explainer for why pharma R&D and manufacturing tends to be located in suburban rather than urban areas. Pharma and biotech R&D and manufacturing operations, are, as they scale in the US, forced to locate in areas (e.g. New Jersey, Chicago suburbs, and Philly suburbs) that are less attractive to talent. If China is able to avoid this tradeoff, due to lower land acquisition and lab construction costs, it will enjoy a real competitive advantage.

On the other hand, the US enjoys a substantial lead in its control over current assay technologies and in its development of next-generation assays. Just as foundries rely on lithography system-makers, the biotech industry relies on a constellation of specialized equipment-makers. To give a sense of how equipment-maker moats compare between semiconductors and biotech, let us compare lithography pioneer ASML with Wyatt Technology, a maker of bioanalytical equipment for life science research. ASML had $30B in revenue in 2023 and 42k employees, so roughly $700k annual revenue per employee. Meanwhile, when Wyatt was acquired by Waters, it reported 2022 revenue of $110M and 200 employees, so roughly $550k annual revenue per employee. In general, the biotech equipment industry is smaller and more fragmented than the semi equipment industry, but with similar pricing power. To develop a drug or biologic, you need a wide array of tools; and not only is your demand inelastic for a type of tool, but you have little choice in suppliers, since each tool is usually a piece of productized academic research. Furthermore, tools are typically fragile and difficult to properly use, requiring frequent assistance. Given America’s multi-decade head start and continued outperformance in the development of new bio-analytical and bio-engineering technologies, it would be difficult for China to quickly catch up in order to survive potential sanctions.

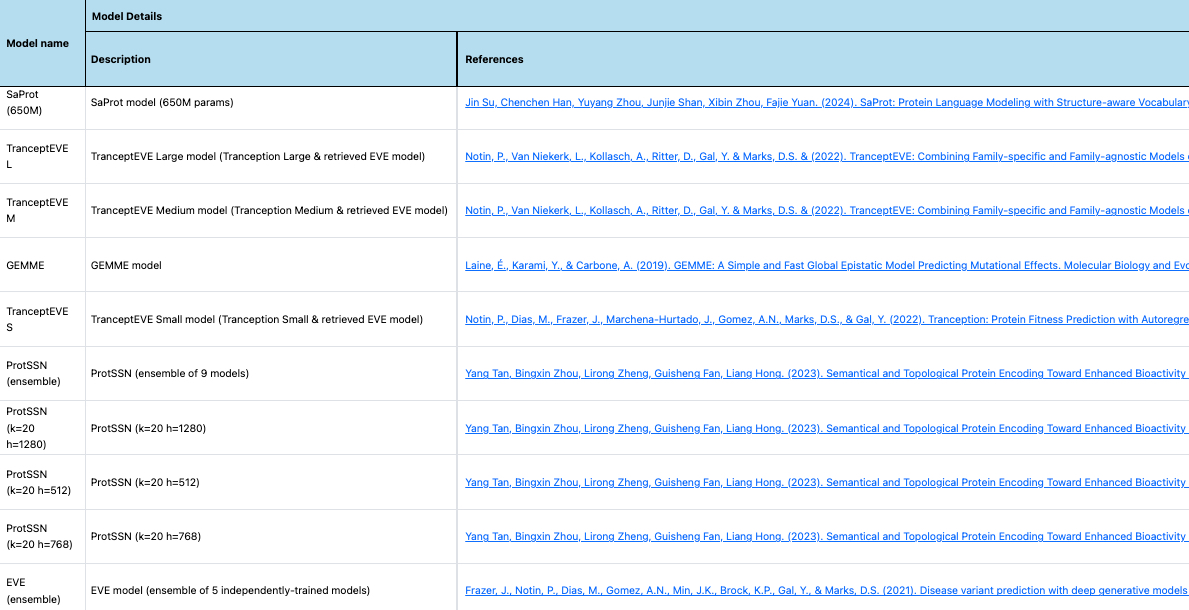

China is at another disadvantage due to semiconductor-related sanctions. If AI is to transform biology, large-scale computing resources will be needed, both to train on large datasets and to run large-scale molecular dynamics simulations. At the current time, in part because current biological datasets are still quite small (e.g. the PDB dataset used to train AlphaFold has only 120k samples), this has not become a disadvantage for China. For example, Chinese teams are doing very well on the Protein Gym benchmark leaderboard as of May 10, 2024.

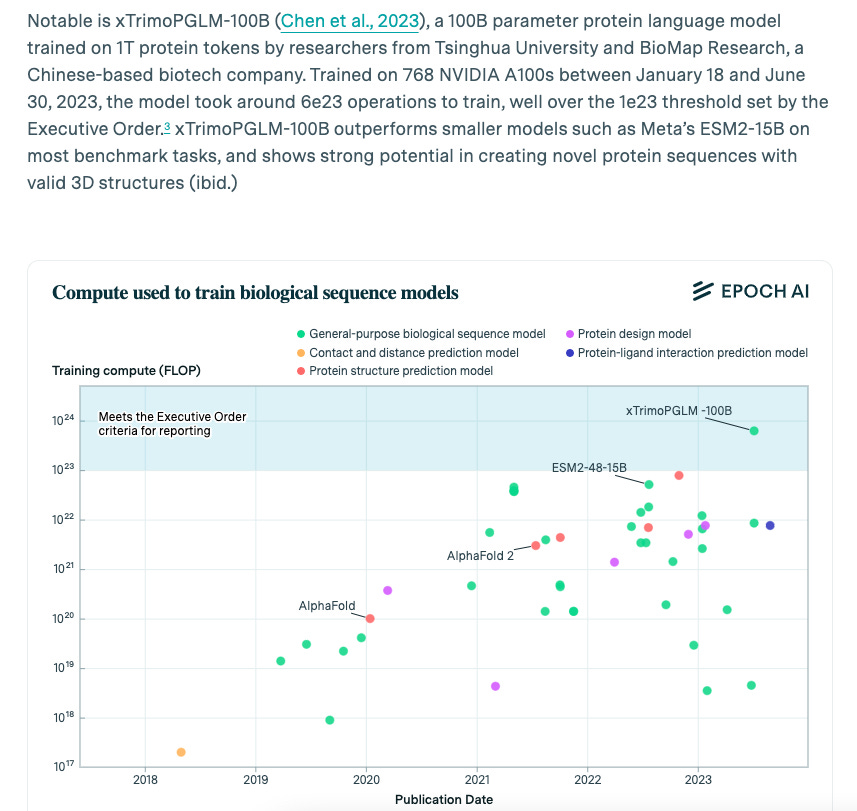

The current largest protein language model, xTrimoPGLM, was trained by a Chinese biotech company, as noted by a recent Epoch AI report. (Note that while XTrimoPGLM goes over the Executive Order limit, training was completed before the EO was issued.)

However, in this case, it’s not clear that xTrimoPGLM was actually trained in China. Indeed, the authorship list and the team page of BioMap Research do not rule out the possibility that it was trained in the US in order to utilize A100s, which received an export ban 2 months prior to training.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that xTrimoPGLM is not simply a big model that wasted a lot of compute. The paper demonstrates innovations in training techniques and reports competently done experiments demonstrating improved model capabilities. This is consistent with a larger phenomenon that has surprised many Western observers: China has talented and innovative scientists and engineers. Western policymakers have recently discovered this about BYD in the EV space and Huawei in the semiconductor space, but this is also true in the LLM space (e.g. DeepSeekAI) and in the biotech space. Western Big Pharma companies have already started sourcing clinical assets from China and forming development alliances with Chinese bio/pharma companies. While China remains behind the US in pursuing new targets / mechanisms of action, it has made enough progress that suggests it will be able to utilize AI towards profitable translational ends.

In summary, if the 21st Century will be defined by revolutions in AI + biology, China has a decent chance of leading such a revolution. It can more easily scale biological data collection operations, while it may struggle to match the US in computing resources until its semiconductor industry catches up with the West. Meanwhile, China is not far behind the US with regards to developing human capital for life science R&D.

Given the potential for AI + biology progress to radically improve human life, it is worth considering whether predicting the geopolitical “winner” is really an important question. But even if it is not — and I personally don’t think it is — the fact that we are likely to see a close race between geopolitical adversaries is cause for optimism. For when acceleration is the vibe, geopolitical competition is low-key goated.

Disclaimer: Views are never more than my own, and indeed are frequently not even my own.